Three Strategies for Working Through Creative Block

So it’s been a while since you’ve sat down to work on your art form. The page or canvas or whatever seems to taunt you – it says, “What’s the big deal? Just make something.” The advice of friends and self-help books echo the blank page’s sentiment – “Just 10 minutes a day! What’s the big deal?” Yeah, okay. It should be easy, right? Sure! What’s 10 minutes in the grand scheme of things?

I should have something to say... right?

But then you sit down to do your 10 minutes and literally have nothing to say, nothing to draw, no movements or sounds to pull from the cavernous expanse where your creative mind used to be.

Time passes.

A few days, a few weeks, a few months, a year. The good advice still rings in your ear – “just 10 minutes a day!” Time is no excuse – you have 10 minutes a day. And then the doubt creeps in: “If I were really a writer, dancer, painter, actor, filmmaker, whatever, then this wouldn’t happen. I should have something to say.”

How long does this go on? Two months? Two years? Three? After year five do you donate the rest of your colored pencils to kids in need and settle into your family life, your job, your other hobbies?

Maybe. Sometimes being true to ourselves requires us to let things go.

But sometimes there’s just something inside that nags, that says, “I’m not okay with quitting. There is something I’m missing when I don’t make art. I do have something to say – I just can’t remember how to get started.”

If this is the case, then it may be helpful to think about some psychological causes of creative block and some tools for focusing when creative block hits.

Strategy 1: work through Creative Block In The Body

For many of us who engage in art practices, our senses of worth and identity are tied up in the practice. This high stakes relationship to art can lead to a lot of fears when we sit down to actually make some art. And unfortunately, when we experience a cascade of fearful thoughts, our bodies often react as though the thoughts are true.

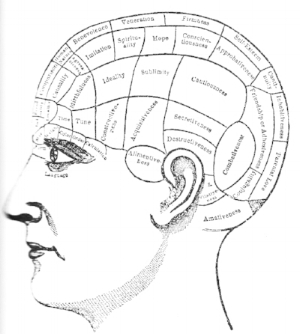

Stress activates and deactivates particular areas of the brain - and not always in a way that is helpful for creativity.

So, for example, if you have thoughts along the lines of, “If I can’t come up with an idea it means I’m not really a painter, which means I'm stuck in my dead-end job forever, which means I’m a failure...” your body would react as though you are a failure. And failure, for some of us, can bring on a full on stress response.

Stress responses, also known as fight/fight/freeze, are necessary for survival, but can be problematic for creativity. A little bit of stress can focus us and enhance creative performance, but a lot of stress can reroute blood flow to the brain in such a way where many functions that are not necessary for basic survival are compromised.

So what does a stress response feel like? It might feel panicky, with rapid shallow breathing and a lot of tension in your muscles. It might feel like an urge to run away – to literally do anything other than what you’re doing right now. It might feel like a sudden surge of anger or resentment, or a general sense of irritability and restlessness. Or it might feel like your mind is blank or numb, or that you feel distracted, immobile, or have suddenly low energy.

No matter which response you are having, if it is impeding your ability to be creative then you may require grounding prior to proceeding with your artistic process.

Grounding

Try orienting yourself to your surroundings. This sends a message to the body that you're safe enough to engage the parts of your brain that aren't specific to survival.

Grounding doesn’t have to be complicated –I think of grounding as any practice that orients your senses to the present moment and reminds your body that you are in a safe place.

Some ideas: Press your feet into the floor and notice the pressure. Take a look around the room and notice the colors and shapes. Name objects in the room to yourself. Listen to the sounds around you. Notice your body posture or breath (if that feels okay).

Or, you could ground by noticing the sounds and textures of the medium you work with. For example: Pluck a string on the guitar and actively listen to it reverberate all the way until it reaches silence. Type a few nonsense words on the keyboard and really notice the feel of the keyboard on your fingertips or the sounds of the keys clacking. Rustle the pages of your script and notice the sound, the feeling of the breeze and the texture of the pages against your fingers. Rub your feet against the studio floor and notice the heat that gets generated, or get curious about the smell of the (non-toxic) paints.

You will know when you are feeling more regulated because your breath will even out, your mind will feel less blank or less freaked out, and your overall sense of willingness to try something will increase.

Strategy 2: work through Creative Block In The Thoughts

In addition to working with the body, it can be helpful to work with the thoughts that come up around art making.

Practice Versus Performance

Paul Klee, Twittering Machine, 1922. We can't necessarily sit down to make a masterpiece. But we can paint, and maybe something great will emerge.

Oftentimes we sit down to make art with grand thoughts of what we are about to do. We might think, “I’m sitting down to write a novel,” or “I’m sitting down to write a song.” How do these thought feel? If they feel manageable and you find it easy to get started, then run with it.

But if you feel anxious or preemptively ashamed about your presumed imminent failure – or more importantly, if the way you're thinking about making art doesn’t help you get started – then it may be more helpful to think about the work a different way.

For example, telling yourself, “I’m here to make a painting,” may make it tougher to start than if you tell yourself, “I’m here to play with color and remember what it feels like to use a paintbrush.” Likewise, if you tell yourself that you’re sitting at the computer to “start a poem,” you may find yourself less available to write than if you tell yourself, “I’m going to generate some text and explore sounds and ideas.”

For many of us, telling us that we’re sitting down to a practice as opposed to sitting down to a performance can lower the stakes, which lowers our anxiety and allows for more freedom of thought.

Getting the Feet Wet

Does even this feel too overwhelming? Then maybe practice for you starts not with creation, but with re-entering the world of the art you make. You could get your feet wet by going to a museum, signing up for a workshop, eavesdropping, picking up a screenplay or collection of poetry, asking a friend to hear the new song they wrote, reading the biography of an artist you admire, or watching a snippet of dance on the internet.

You will know in your heart of hearts when you are dallying in “research” instead of beginning to reenter the world of making.

The Importance of Beginning at the Beginning

Wherever your starting point is, it is crucial to remind yourself that there is no such thing as wasted effort when it comes to art making. I like to think of these beginning stages as creating the primordial ooze that some unforeseeable mammal will emerge from in the future. If we skip the ooze stage... no mammal. If we force the ooze to be a mammal... sad, dead misshapen mammal.

AND, if making art is something that brings meaning to your life, maybe you have to begin to accept that sometimes there might just be ooze – no mammal – for a little while. Just to engage with the art invites into our lives a complexity of experience that avoidance does not bring, even if a final product is currently nowhere to be seen.

Strategy 3: work through creative block as a practice

Once you get over the initial hump of putting pen to proverbial paper, you may continue to experience doubts and intrusive thoughts about where the project is going, what you should be doing instead, your worth as an artist or a human being, chores, your ex, etc. It can therefore be helpful to use some tenants from mindfulness practice to help yourself both stay focused and hold compassion for yourself.

What is Mindfulness Practice

If we don't hold on too tight, we can often let our thoughts come and go like waves.

The practice of mindfulness is simple on paper: we choose what is called an “anchor,” and practice returning our attention to that anchor over and over again when thoughts, sensations and other phenomena draw our awareness away. The anchor can be anything that it’s possible to pay attention to. It can be our breath, a sound, the feeling of our feet on the ground. The practice isn’t so much about staying focused, but rather about noticing when we are no longer focused and gently, non-judgmentally bringing ourselves back to paying attention the anchor, just as it is in the present moment.

We can easily take the concept of mindfulness meditation and apply it to an art making practice. The practice is your anchor. Your job is notice when you’ve wandered, name where you went, and then gently bring yourself back to your practice.

Here’s how that might go:

If you sat down to draw cats, just draw cats. Anything else can wait.

You’re sitting down to work on a monologue you’d like to perform, and 60 seconds in, you start thinking about how you should have worked harder when you were in college because then you’d be further along in your career now. Poof – you’ve left the practice. As soon as you notice you’re gone, you can say to yourself, “regret,” and gently bring your attention back to the monologue.

A minute later you remember that you wanted to paint your bathroom and begin to wonder whether blue or white would look better... poof. You’ve left the practice. You can say to yourself, “housework thoughts,” and gently bring yourself back to working on the monologue.

Suddenly you’re worrying that your time would be better spent watching a video of someone else performing this monologue, or practicing yoga instead of working on a monologue, or networking, or looking for an agent, or literally anything else tangentially related to being an actor. Poof. You’re gone. You can say to yourself, “doubts,” and gently bring yourself back to the task at hand.

You work a little more, and then find that you’ve begun to fantasize about founding your own troupe of actors and going on the road with a performance of the play that contains this monologue. Poof – you’re gone again. You can say to yourself, “ambitious idea,” jot down the idea if you want, and gently bring yourself back to the monologue. Ideas – especially ambitious ideas – can be especially disruptive as it can be tricky to distinguish between ideas that are useful for your process and ideas that are more about anxious thinking and putting the proverbial cart before the horse. It can be useful to keep a notepad for these ideas and just jot down the gist of them, giving yourself permission to return to them later, after you have finished the task at hand, which is your immediate art practice.

Your practice is your anchor.

Make sense? We choose an art-making task and return to it over and over. Everything else can either be gently set aside for good or jotted down so you can come back to it later. As with mindfulness practice, a successful practice isn’t about annihilating those kinds of thoughts, but rather about catching yourself in them and gently bringing yourself back.

Frustrating? Of course. But just like with mindfulness meditation, this process of continuously bringing yourself back can be deeply rewarding. Over time, we develop focus, courage and compassion. And ultimately, it means that at the end of the 10 minutes (or whatever), we’ve actually worked on our art.

bonus strategy: Rewarding Yourself

After you get through the initial block and successfully engage in your art practice, try rewarding yourself. The reasoning? We're more likely to repeat behaviors when they're rewarded.

The reward can be tangible, like a cuddle with the dog, making avocado toast, calling up a friend to hang out, watching youtube videos about bower birds, or even researching paint colors for the bathroom. Whatever feels rewarding to you.

Or, the reward can be a simple acknowledgement of yourself. You can let yourself know that you have done something to add texture to your world. You can let yourself know that you were brave to face your creative block. You can remind yourself why art is important to you, and celebrate that you set aside any amount of time for art, especially when the world makes it so easy to stay over-focused on errands, to-do lists, politics, friend drama, whatever.

You can remind yourself that just by setting aside 10 minutes to engage creatively with yourself and the world, you have introduced a tiny act of resistance, healing, and beautification.

And who knows where that could lead.

Onwards!